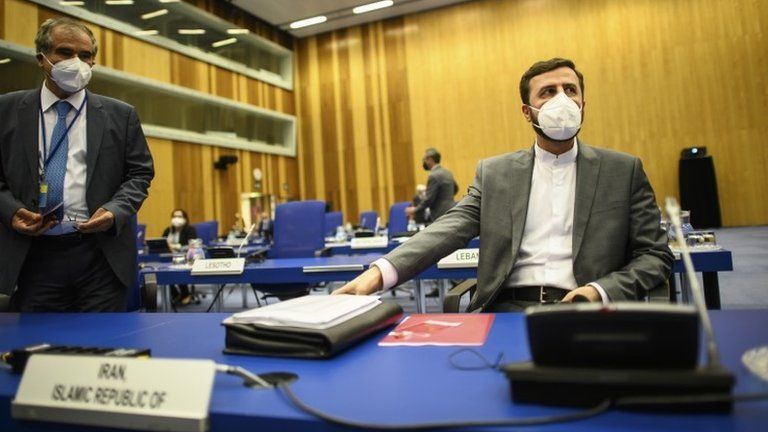

IMAGE SOURCE, AFP Image caption, Iran agreed to allow continuous and robust monitoring by the IAEA as part of the 2015 nuclear deal

By David Gritten

BBC News

It comes after the International Atomic Energy Agency’s board censured Iran for not answering questions about uranium traces found at three undeclared sites.

IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi said 40 cameras would remain, but that the move posed a “serious challenge”.

Unless it was reversed within three to four weeks, he warned, it would deal a “fatal blow” to the Iran nuclear deal.

Under the 2015 agreement with world powers, Iran agreed to limit its nuclear activities and allow continuous and robust monitoring by the IAEA’s inspectors in return for relief from economic sanctions.

However, it has been close to collapse since the US pulled out unilaterally and reinstated sanctions four years ago and Iran responded by breaching key commitments.

On Wednesday, the IAEA’s 35-nation board of governors approved a resolution that expressed “profound concern that the safeguards issues” related to the undeclared sites “remain outstanding due to insufficient substantive co-operation by Iran”. It also urged the country to “act on an urgent basis to fulfil its legal obligations”.

But the Iranian foreign ministry denounced it as a “political, unconstructive and incorrect action”.

Spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh tweeted that the Western powers had “put their short-sighted agenda ahead of [the] IAEA’s credibility” and that they were “responsible for the consequences”.

“Iran’s response is firm & proportionate,” he added.

IMAGE SOURCE, EPA

IMAGE SOURCE, EPAIran has been withholding footage from the IAEA’s cameras for the past year in an attempt to increase pressure on the US at the negotiating table.

On Thursday, Mr Grossi said he had been informed that Iran was removing “basically all” of the cameras and other monitoring equipment that were installed under a 2003 agreement on inspections, implemented months after Iran’s secret nuclear sites were exposed.

“This, of course, poses a serious challenge to our ability to continue working there and to confirm the correctness of Iran’s declaration under the [deal],” he told reporters.

The 40 cameras remaining were installed under a safeguards agreement that was completed by Iran after it signed the nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1970

Mr Grossi warned that the removal of the cameras would deal a “fatal blow” to the nuclear deal unless it was reversed in the next three to four weeks because the IAEA would no longer be able to maintain a “continuity of knowledge” about Iran’s nuclear activities and material.

IMAGE SOURCE, ANADOLU AGENCY

IMAGE SOURCE, ANADOLU AGENCYIran insists its nuclear programme is entirely peaceful and that it has never sought nuclear weapons, but evidence collected by the IAEA suggests that until 2003 it conducted activities relevant to the development of a nuclear bomb.

The IAEA’s board voted to censure Iran after the director general told a meeting on Monday that he was still unable to confirm the correctness and completeness of Iran’s declarations under the Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement (1974) and Additional Protocol (2003).

He said that was because Iran had “not provided explanations that are technically credible in relation to the agency’s findings at three undeclared locations”, which he named as Turquzabad, Varamin and Marivan.

According to the IAEA’s latest report, environmental samples taken by inspectors at the three locations in 2019 or 2020 indicated the presence of “multiple natural uranium particles of anthropogenic [man-made] origin”.

Mr Grossi said Iran had also not informed the IAEA “of the current location, or locations, of the nuclear material and/or of the equipment contaminated with nuclear material, that was moved from Turquzabad in 2018”.

The director of the Atomic Energy Organisation of Iran (AEOI), Mohammad Eslami, insisted on Wednesday that his country had “no hidden or undocumented nuclear activities or undisclosed sites”.

Iran had maintained “maximum co-operation” with the IAEA, he said, adding that “fake documents” had been passed to the watchdog as part of a “maximum pressure” strategy provoked by Israel, its arch-enemy.

An AEOI spokesman confirmed it had told the IAEA the three locations could have been deliberately contaminated as an act of sabotage by a third party.

Mr Grossi also warned on Monday that Iran was “just a few weeks” away from having stockpiled enough enriched uranium to create a nuclear bomb. Enriched uranium is used to make reactor fuel, but also nuclear weapons.

The IAEA’s latest report said Iran had 43.1kg (95lb) of uranium enriched to 60% purity, which Kelsey Davenport of the US-based Arms Control Association said could be enriched to 90%, or weapons-grade, in under 10 days. However, Ms Davenport noted that “weaponization” – manufacturing a nuclear warhead for a missile – would still take one to two years.

-

IAEA urges Iran to explain uranium traces at sites

7 June 2021

-

Iran nuclear crisis in 300 words

16 November 2021